This info came from |

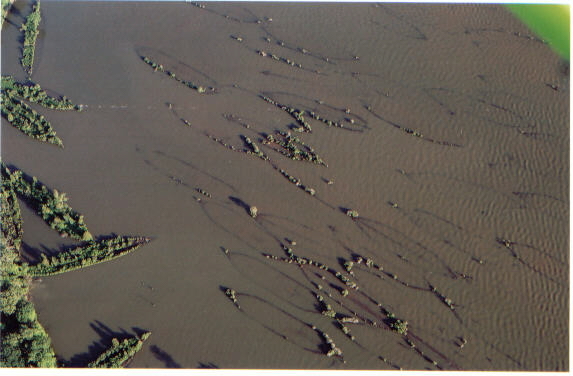

The Ships in the Graveyard Just offshore of Charles County, Md., lies one of the Potomac River's great historical oddities. From a distance, the water's surface is broken by patches of low scrub covered islands seemingly overcome by the tide. On closer inspection, the islands have distinct outlines, familiar forms, and an arrangement unusual to behold in most quiet coves along the Potomac. This is Mallows Bay, the resting place of some 130 sunken ships, including the remains of 81 historically significant wooden steamships built under a crash government program during World War I. For decades, the mile-long isolated cove about 30 miles south of Washington has served as a dumping ground for old ships. And for almost half a century the site has been virtually ignored by all with the exception of wildlife and the anglers. Today historians, conservationists and many citizens are interested in designating the area as a special shipwreck preserve to maintain this unique historical site. According to Don Shomette, a maritime historian and underwater archeologist, Mallows Bay holds the greatest concentration of sunken ships in North America. "It's one of our stunning and undiscovered resources," said Shomette. The diverse collection of ships at the site includes various sailing vessels, steamships, and even an 18th-century longboat, which also is the oldest wreck in the cove. The main attraction at Mallows Bay is the steamship fleet. During World War I, the United States built a fleet of 336 wooden steamships intending to use them in the war against Germany. The hulking, coal-dependent ships ranged from 265 to 285 feet long and cost more than $1 billion to construct. However, it was soon discovered that the long transatlantic journey required so much coal that the ships could not carry much cargo and the steamships were rendered obsolete by the time the war was over in 1918. In the early 1920s, the majority of the fleet was sold to a variety of investors for scrap material and by the 1940s, most of the hulls had been salvaged by prospectors, burned to their waterlines and abandoned. Although it is difficult to access the site - the shoreline is privately owned and protruding debris threatens the hull of any craft larger than a canoe or kayak - officials from the State of Maryland and Charles County have been interested in making Mallows Bay the second historic shipwreck preserve in Maryland. An existing preserve for a German U-boat has already been established off the coast of St. Mary's County, Md. on the lower Potomac. By law, the state already owns any historic artifacts in tidal waters including the wrecks. If established, the costs for the preserve would be limited to signs, brochures and possibly buoys to mark the wrecks. However, the state is also exploring options to purchase some land along the shoreline and establishing a park where the public could view the wrecks and take advantage of some interpretative displays about them. Richard Hughes, chief of archeology at the Maryland Historical Trust has said that if all goes well, Mallows Bay could be declared a preserve as soon as next year with or without shoreline access. The interest is centered on preserving the unique character of the site and possibly set up research projects related to the wrecks. Shomette notes that there is interest in preparing and setting up a long term study to determine the effects of environment on shipwreck disintegration at Mallows Bay. Though the hulls have been inventoried, there has been no in-depth survey of their contents or attempt to retrieve artifacts due to limited funds. Representatives from the state say that although they are interested in acquiring the site, Mallows Bay is still only one of many sites being considered for the purchase with the state's somewhat limited funds for waterfront acquisitions. The history and ships of the bay are the subject of a new book by Shomette entitled "The Ghost Fleet of Mallows Bay," available from Tidewater Publishers. |

This info came from |